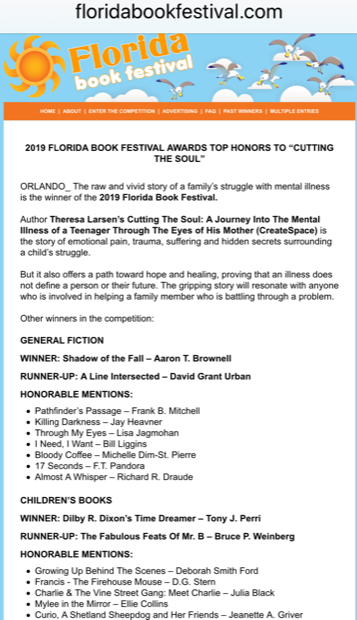

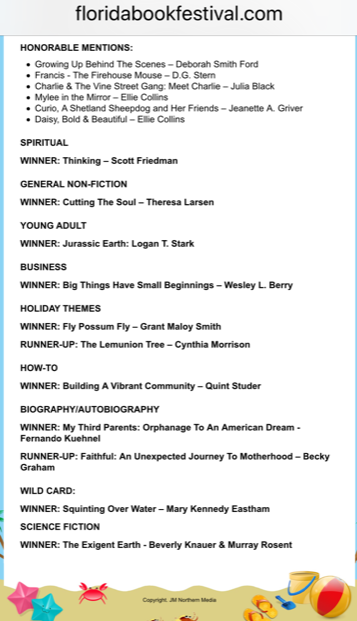

Awards for Cutting the Soul

Grand Prize and Non-Fiction Winner at the Florida Book Festival-2019

B.R.A.G. Medallion Honoree-

www.bragmedallion.com/medallion-honorees/2015-brag-medallion-books/cutting-the-soul

Honorary Mention for Non-Fiction at The Great Southeast Book Festival-2015

* SELF-HARM TRIGGER WARNING*

Theresa Larsen’s son,

Matthew, comes to her with a cut on his hand, explaining it away as an accident

with a pocket knife. But as she cleans and treats the wound, she discovers

dozens of slashes covering both of his arms. Thus begins Larsen's compelling

personal memoir about what it's like to be the parent of a mentally ill

teenager.

Cutting the Soul offers a firsthand look at mental illness, both financially and emotionally. Matthew, fourteen years old when he starts cutting, goes on to face other hardships, including suicide attempts, severe depression, and multiple stays in psychiatric hospitals.

Readers get an inside look at Matthew's life through the inclusion of his selected journal entries, and Larsen shares her own struggles with personal demons as she tries to help her son. It's a first-person account and an educational guide worth reading for any parent who’s coping with the mental illness of a child.

Cutting the Soul offers a firsthand look at mental illness, both financially and emotionally. Matthew, fourteen years old when he starts cutting, goes on to face other hardships, including suicide attempts, severe depression, and multiple stays in psychiatric hospitals.

Readers get an inside look at Matthew's life through the inclusion of his selected journal entries, and Larsen shares her own struggles with personal demons as she tries to help her son. It's a first-person account and an educational guide worth reading for any parent who’s coping with the mental illness of a child.

Reviews and Comments

5* Review by Megan Riddle at Psych Central, an online mental health resource

It is late on a Friday night in the emergency department as I lead the mother into a small family room off the hallway. She is here with her son, who is now sitting in the locked psychiatric wing of the ER. We sit down on the threadbare couches.

“Tell me,” I say, “what’s been going on.” Out pours a tale of a successful young man, off to college, his bright future ahead of him — then the gradual deterioration, the precipitous decline. Now, instead of sitting in an auditorium at graduation, the mother tells me, she is sitting in the ER, holding back tears. This is not the future she envisioned for her child.

Mothers of those with mental illness share a special burden that they rest of us can only begin to imagine. They have raised and loved a person, but that person seems to have disappeared. In her book, Cutting the Soul: A Journey into the Mental Illness of a Teenager Through the Eyes of His Mother, Theresa Larsen offers us an intimate look at the experience.

At fourteen, Larsen’s son Matthew had a “subtle” intelligence. “Sensitive and kind,” he “had high expectations and unrealistic goals,” taking advanced classes and serving as the sweet older brother for his little sister. Over the course of a few months, his mood began to sink. Sometimes he isolated himself; other times, he seemed like the Matthew his mother knew.

Then one day, he came to her, apologizing. “Mom, I cut my hand,” Larsen recalls him saying. “… Don’t be angry with me please. I was messing around with my pocket knife and I cut my hand. I didn’t mean to cut it this deep.” It was the cry of a confused, distressed boy, and set both Larsen and her husband, Erik, grappling for words as they clean his wounds.

“Were you trying to kill yourself?” Erik asked.

Matthew flatly denied it. But while the cuts were not so deep as to require an immediate trip to the ER, Larsen realized they represented something far deeper. After a trip to their pediatrician, she sought out mental health treatment for her son. Thus began a disastrous series of psychiatrist visits that would make anyone in the profession cringe and want to offer her an apology.

The cutting continued. “I couldn’t help it,” Matthew told his mother. “I don’t know what to do.”

Larsen intersperses Matthew’s own journal entries from the time, giving us a glimpse into his thought process. “Only a single action can relieve me of my misery, but it has been forbidden,” he writes. “Like a match it takes a few strikes to spark my courage.”

Desperately, Larsen continued to seek answers. After trying to avoid medications for Matthew as long as possible, she realized she had to. “I needed the prescription to work,” she writes, “or Matthew’s illness was going to destroy our family.”

Matthew continued to deteriorate. His self-harm progressed to suicide attempts, his thoughts devolved into psychosis. He was hospitalized, then in residential treatment. After cutting himself with a sharp plastic object he found while in residential treatment, he writes, “This is actually the first time I wanted to cut to kill. An attempt to murder myself. I wish it worked. Damn it. … The pain I cause my parents. They hurt because of me. I cry knowing how much hurt it causes them to see me like this. I must stop! I must! I will, damn it!” But he cannot stop, and it is quite some time before he or his family find relief.

These journal entries, alongside Larsen’s own words, show us both what the son and the mother have gone through. Brushes with others with mental illness — a young man who tried to break into their house; a shooter at their daughter’s school — all made Larsen wonder what the future held for Matthew. In therapy herself, she asked, “How do I cope with Matthew dying?” As a mother, she writes, “Constantly waiting for my phone to ring with more bad news, kept me in a state of perpetual crisis.”

Larsen honestly depicts the tight-rope of fear and worry that parents in her shoes must traverse every day, balancing their own needs and those of the family at large with those of the mentally ill member.

“Maybe you need to redefine what normal is,” one of Matthew’s therapists offered at one point.

As I saw with the mother I spoke with in the ER, having a mentally ill child means redefining many things. For anyone who has had a mentally ill family member, you know there is rarely (never?) a happily ever after ending.

There is, however, a happier for now.

For Matthew and his family, the new normal, while maybe not the original plan, is one filled with hope and possibility. “Reach out and grasp hold of everything you once knew,” Matthew writes in his journal. “A love for this contentment festers inside you. Unlock the potential your life now holds.”

It is late on a Friday night in the emergency department as I lead the mother into a small family room off the hallway. She is here with her son, who is now sitting in the locked psychiatric wing of the ER. We sit down on the threadbare couches.

“Tell me,” I say, “what’s been going on.” Out pours a tale of a successful young man, off to college, his bright future ahead of him — then the gradual deterioration, the precipitous decline. Now, instead of sitting in an auditorium at graduation, the mother tells me, she is sitting in the ER, holding back tears. This is not the future she envisioned for her child.

Mothers of those with mental illness share a special burden that they rest of us can only begin to imagine. They have raised and loved a person, but that person seems to have disappeared. In her book, Cutting the Soul: A Journey into the Mental Illness of a Teenager Through the Eyes of His Mother, Theresa Larsen offers us an intimate look at the experience.

At fourteen, Larsen’s son Matthew had a “subtle” intelligence. “Sensitive and kind,” he “had high expectations and unrealistic goals,” taking advanced classes and serving as the sweet older brother for his little sister. Over the course of a few months, his mood began to sink. Sometimes he isolated himself; other times, he seemed like the Matthew his mother knew.

Then one day, he came to her, apologizing. “Mom, I cut my hand,” Larsen recalls him saying. “… Don’t be angry with me please. I was messing around with my pocket knife and I cut my hand. I didn’t mean to cut it this deep.” It was the cry of a confused, distressed boy, and set both Larsen and her husband, Erik, grappling for words as they clean his wounds.

“Were you trying to kill yourself?” Erik asked.

Matthew flatly denied it. But while the cuts were not so deep as to require an immediate trip to the ER, Larsen realized they represented something far deeper. After a trip to their pediatrician, she sought out mental health treatment for her son. Thus began a disastrous series of psychiatrist visits that would make anyone in the profession cringe and want to offer her an apology.

The cutting continued. “I couldn’t help it,” Matthew told his mother. “I don’t know what to do.”

Larsen intersperses Matthew’s own journal entries from the time, giving us a glimpse into his thought process. “Only a single action can relieve me of my misery, but it has been forbidden,” he writes. “Like a match it takes a few strikes to spark my courage.”

Desperately, Larsen continued to seek answers. After trying to avoid medications for Matthew as long as possible, she realized she had to. “I needed the prescription to work,” she writes, “or Matthew’s illness was going to destroy our family.”

Matthew continued to deteriorate. His self-harm progressed to suicide attempts, his thoughts devolved into psychosis. He was hospitalized, then in residential treatment. After cutting himself with a sharp plastic object he found while in residential treatment, he writes, “This is actually the first time I wanted to cut to kill. An attempt to murder myself. I wish it worked. Damn it. … The pain I cause my parents. They hurt because of me. I cry knowing how much hurt it causes them to see me like this. I must stop! I must! I will, damn it!” But he cannot stop, and it is quite some time before he or his family find relief.

These journal entries, alongside Larsen’s own words, show us both what the son and the mother have gone through. Brushes with others with mental illness — a young man who tried to break into their house; a shooter at their daughter’s school — all made Larsen wonder what the future held for Matthew. In therapy herself, she asked, “How do I cope with Matthew dying?” As a mother, she writes, “Constantly waiting for my phone to ring with more bad news, kept me in a state of perpetual crisis.”

Larsen honestly depicts the tight-rope of fear and worry that parents in her shoes must traverse every day, balancing their own needs and those of the family at large with those of the mentally ill member.

“Maybe you need to redefine what normal is,” one of Matthew’s therapists offered at one point.

As I saw with the mother I spoke with in the ER, having a mentally ill child means redefining many things. For anyone who has had a mentally ill family member, you know there is rarely (never?) a happily ever after ending.

There is, however, a happier for now.

For Matthew and his family, the new normal, while maybe not the original plan, is one filled with hope and possibility. “Reach out and grasp hold of everything you once knew,” Matthew writes in his journal. “A love for this contentment festers inside you. Unlock the potential your life now holds.”

5* Review by Hayes and Norma Basford (NAMI president, Jacksonville)

Mental illness is a cruel affliction. It happens to very bright and creative individuals. It frequently strikes when people are young and at a critical point in their development of setting goals based on their special gifts and abilities. Those who have not dealt with mental illness firsthand have no "clue" about the devastation and chaos that these illnesses create in the individual who has them and the families who are meeting, head on, the seemingly impossible challenges of the loved one who is ill.

Theresa Larson's book is an excellent and heart -rending documentation of life for a young man who has been stricken with a severe biochemical brain disorder. It clearly shows the trauma experienced by the one who lives with the illness and the trauma experienced by a parent who is literally fighting for the life of her son.

This book should be required reading for the general population...those who need to understand these illnesses that are often hidden because of the shame, guilt, stigma and discrimination that is imposed on those who live with mental illness and their families. It should be read by legislators and by national, state and community leaders who have the power to change a system that is so terribly inadequate in meeting the need that is becoming increasingly more evident. Our society continues to experience the tragedies of mass shootings in schools, churches, theaters, military bases , etc. by individuals who have left a trail of obvious, yet ignored or medically underserved, symptoms of mental impairment and have slipped through the cracks of a broken mental health system. Urgent system change is a desperate need as expressed in this author's struggle for assistance!

My husband and I both read the book and greatly admire Theresa Larsen for being one who helps in breaking the chain of silence, for her gifted writing, for her compassion, for her perseverance in never, ever giving up on her son and for perpetuating hope that must be maintained in the hearts of those who meet similar challenges every day. Thank you, Theresa Larsen, and praise to your son for continuing the hard work toward wellness!!

Mental illness is a cruel affliction. It happens to very bright and creative individuals. It frequently strikes when people are young and at a critical point in their development of setting goals based on their special gifts and abilities. Those who have not dealt with mental illness firsthand have no "clue" about the devastation and chaos that these illnesses create in the individual who has them and the families who are meeting, head on, the seemingly impossible challenges of the loved one who is ill.

Theresa Larson's book is an excellent and heart -rending documentation of life for a young man who has been stricken with a severe biochemical brain disorder. It clearly shows the trauma experienced by the one who lives with the illness and the trauma experienced by a parent who is literally fighting for the life of her son.

This book should be required reading for the general population...those who need to understand these illnesses that are often hidden because of the shame, guilt, stigma and discrimination that is imposed on those who live with mental illness and their families. It should be read by legislators and by national, state and community leaders who have the power to change a system that is so terribly inadequate in meeting the need that is becoming increasingly more evident. Our society continues to experience the tragedies of mass shootings in schools, churches, theaters, military bases , etc. by individuals who have left a trail of obvious, yet ignored or medically underserved, symptoms of mental impairment and have slipped through the cracks of a broken mental health system. Urgent system change is a desperate need as expressed in this author's struggle for assistance!

My husband and I both read the book and greatly admire Theresa Larsen for being one who helps in breaking the chain of silence, for her gifted writing, for her compassion, for her perseverance in never, ever giving up on her son and for perpetuating hope that must be maintained in the hearts of those who meet similar challenges every day. Thank you, Theresa Larsen, and praise to your son for continuing the hard work toward wellness!!

5 Star Review by Clinical Psychologist David Susman, PhD http://davidsusman.com/

Theresa Larsen's story of her son's tremendous struggle with serious mental illness is gripping and I found myself getting very emotional at times as I read it. As a mental health professional, I have certainly seen my share of similar issues, but her account was very impactful. She shows considerable courage and openness in sharing openly all that she and her family have gone through. Larsen includes first person "journal" entries written by her son, which added a real, honest element to show what he was experiencing. This story is an awesome testament to the power of unwavering family support in helping someone heal and recover. It is also a wonderful endorsement of the vital importance of intensive and effective long-term treatments for severe mental illness. The book is an inspiration for the many families that are going through similar challenging journeys. At its heart, the story is one of recovery for it shows that recovery is possible even when sometimes it may seem that all hope is lost. It shows that having a mental illness does not define a person nor does it prevent them from having a bright future.

I think the book could be very educational for students preparing for mental health careers as well as for professionals, families and individuals with mental illness. Highly recommended.

Theresa Larsen's story of her son's tremendous struggle with serious mental illness is gripping and I found myself getting very emotional at times as I read it. As a mental health professional, I have certainly seen my share of similar issues, but her account was very impactful. She shows considerable courage and openness in sharing openly all that she and her family have gone through. Larsen includes first person "journal" entries written by her son, which added a real, honest element to show what he was experiencing. This story is an awesome testament to the power of unwavering family support in helping someone heal and recover. It is also a wonderful endorsement of the vital importance of intensive and effective long-term treatments for severe mental illness. The book is an inspiration for the many families that are going through similar challenging journeys. At its heart, the story is one of recovery for it shows that recovery is possible even when sometimes it may seem that all hope is lost. It shows that having a mental illness does not define a person nor does it prevent them from having a bright future.

I think the book could be very educational for students preparing for mental health careers as well as for professionals, families and individuals with mental illness. Highly recommended.

4 Star review by Tabrizia Jones https://cupofteawiththatbookplease.wordpress.com/2015/08/05/book-review-cutting-the-soul-a-memoir-by-theresa-larsen/

Theresa Larsen's uphill battle with her son's mental illness emotionally and beautifully discusses an issue that unfortunately doesn't get the attention that it deserves. I'm not saying that this was not an easy read and I'm not just discussing the uncomfortable and descriptive details of Matthew's trials. But difficult for someone who has suffered through mental illness, like myself. I needed to read this, not just to be informed, but for my own well being. Like both Matthew and Theresa discovered, I wasn't alone in my struggles.

Usually when you read about mental illness, it's always in the point of view of, in this case I will say, the patient. So it is refreshing to read someone's experience dealing with a close relative's mental illness. When you hear about a person suffering through depression and other mental disorders, you always concentrate on how it is affecting that person, but you rarely think twice on how it affects the whole family. You truly don't understand the physical and emotional toil it puts on a family, the financial burden that they have to go through. When reading this memoir, it is a huge eye opener. Reading about Larsen's experiences proves why this issue needs to be openly discussed and backed, especially from insurance companies. This is an important issue that just cannot be set aside.

Larsen's emotions are radiating from these pages. You can feel her pain when she sees her son at his worst. You can feel her frustration when she sometimes loses hope. You can feel her fear when she thinks that every time she visits her son it will be for the last time. I applaud Larsen for writing Matthew's and her family's struggles. It must be very difficult for her to relive these painful experiences. But I think it was necessary. It might have been cathartic for her but her story needed to be told for others to know that you are not alone in this and there's hope at the end of the tunnel.

Larsen refers back to Matthew's writings from his journal and even though it was uncomfortable to read at times due to its dark nature, I believe it was very important. You are reading what Larsen is going through which is vital, but you need to know what Matthew is going through in his own words and you get that through his journal writings.

If you are uncomfortable reading about dark, personal matters, then this memoir may not be for you. But I hope you change your mind because in my opinion, I feel that this is a type of book that everyone should read. This is an important issue that should definitely not be bypassed.

Theresa Larsen's uphill battle with her son's mental illness emotionally and beautifully discusses an issue that unfortunately doesn't get the attention that it deserves. I'm not saying that this was not an easy read and I'm not just discussing the uncomfortable and descriptive details of Matthew's trials. But difficult for someone who has suffered through mental illness, like myself. I needed to read this, not just to be informed, but for my own well being. Like both Matthew and Theresa discovered, I wasn't alone in my struggles.

Usually when you read about mental illness, it's always in the point of view of, in this case I will say, the patient. So it is refreshing to read someone's experience dealing with a close relative's mental illness. When you hear about a person suffering through depression and other mental disorders, you always concentrate on how it is affecting that person, but you rarely think twice on how it affects the whole family. You truly don't understand the physical and emotional toil it puts on a family, the financial burden that they have to go through. When reading this memoir, it is a huge eye opener. Reading about Larsen's experiences proves why this issue needs to be openly discussed and backed, especially from insurance companies. This is an important issue that just cannot be set aside.

Larsen's emotions are radiating from these pages. You can feel her pain when she sees her son at his worst. You can feel her frustration when she sometimes loses hope. You can feel her fear when she thinks that every time she visits her son it will be for the last time. I applaud Larsen for writing Matthew's and her family's struggles. It must be very difficult for her to relive these painful experiences. But I think it was necessary. It might have been cathartic for her but her story needed to be told for others to know that you are not alone in this and there's hope at the end of the tunnel.

Larsen refers back to Matthew's writings from his journal and even though it was uncomfortable to read at times due to its dark nature, I believe it was very important. You are reading what Larsen is going through which is vital, but you need to know what Matthew is going through in his own words and you get that through his journal writings.

If you are uncomfortable reading about dark, personal matters, then this memoir may not be for you. But I hope you change your mind because in my opinion, I feel that this is a type of book that everyone should read. This is an important issue that should definitely not be bypassed.

4 Star review-- Mother's Courageous Story

Theresa Larsen is to be commended for her courage in writing a book in which she has opened her heart and personal life to the world. Her son Matthew's mental illness is explored, as well as the possible reasons for its development. Entries from Matthew's own journal are interspersed throughout his mother's narrative and are nightmarish and truly chilling and frightening to read.

Not only those who are part of a family dealing with mental illness should read this book. Everyone should read it. The book would open many people eyes to the trauma of this type of illness. There is far too great a stigma attached to mental illness in our society. Those afflicted with mental illness not only have to struggle with the devastation in their own lives and the lives of their loved ones but also have to deal with prejudice and misconceptions of others. Even those who are suffering mental illness themselves have self-stigma and feel they are failures and that they are responsible for bringing heartbreak to their families when it's their illness that's responsible.

The book goes into the difficulties in finding the correct course of treatment and the high cost of treatment. Much reform is needed to address the health needs of the mentally ill. Parents need better options when their child first exhibits signs of mental problems.

My prayers to this family that their days ahead will be happy and healthy ones.

This book was given to me by the author in return for an honest review.

Theresa Larsen is to be commended for her courage in writing a book in which she has opened her heart and personal life to the world. Her son Matthew's mental illness is explored, as well as the possible reasons for its development. Entries from Matthew's own journal are interspersed throughout his mother's narrative and are nightmarish and truly chilling and frightening to read.

Not only those who are part of a family dealing with mental illness should read this book. Everyone should read it. The book would open many people eyes to the trauma of this type of illness. There is far too great a stigma attached to mental illness in our society. Those afflicted with mental illness not only have to struggle with the devastation in their own lives and the lives of their loved ones but also have to deal with prejudice and misconceptions of others. Even those who are suffering mental illness themselves have self-stigma and feel they are failures and that they are responsible for bringing heartbreak to their families when it's their illness that's responsible.

The book goes into the difficulties in finding the correct course of treatment and the high cost of treatment. Much reform is needed to address the health needs of the mentally ill. Parents need better options when their child first exhibits signs of mental problems.

My prayers to this family that their days ahead will be happy and healthy ones.

This book was given to me by the author in return for an honest review.

5 star review by Nathan Mercer

Cutting the Soul: A journey into the mental illness of a teenager through the eyes of his mother by Theresa Larsen was a difficult book to get through. I don't mean writing style, grammar, or something mundane like that. I mean the subject matter. Theresa writes of her year's long battle against her son's mental illness that manifested in cutting and suicidal thoughts.

I could feel how taxed, exasperated, and at wit's end this mother was through the pages. I kept having to check how much was left in the e-book because I was getting to the point where I wasn't sure I could keep going back for more - and I didn't have to live it. How Larsen was able to sit down and relive the darkest of days to actually finish this book is a testament to how devoted she is to helping others who are going through this.

Having been a high school teacher, I am familiar with the different ways kids can "self-harm" - reading this gave me an insight as to just how horrific a cost it is to the entire family. The amount of doctors, facilities, high schools, and medications that had to be juggled were enough to break down even the strongest willed person.

Throughout the book, Larsen refers back to her son's journal, giving everyone a glimpse into the mind of the person who is suffering. These were by far the hardest passages for me to read. As an outsider, it is easy to look at these kinds of situations and think - "that person just needs to snap out of it" - or - "why don't the parents do something to stop this?" Unfortunately, the answer is neither that simple or logical.

I applaud Larson for putting her story out there for others who might have to travel down this road. If you have a teenager who is depressed or self-harms, this book will let you know that you are not alone. Larsen could literally save you a small fortune by her insights as to what to look for in a facility.

More importantly, this book should give you hope. I am not going to call this a "spoiler," because a happy ending should not "spoil" anyone's day. In the end, Matthew seems to have gotten to a point where things were looking much brighter. There were parts of me preparing to read an end to this story that I really did not want to imagine. To Matthew's credit, along with the Larsen family who supported him along the way, that is a plot line that can hopefully stay forever in the "delete" file.

To Theresa, Matthew, and the rest of your family - my hope is that you may have many more good days than bumps in the road in your future.

http://moviesandmanuscripts.blogspot.com/search?q=theresa+larsen

Cutting the Soul: A journey into the mental illness of a teenager through the eyes of his mother by Theresa Larsen was a difficult book to get through. I don't mean writing style, grammar, or something mundane like that. I mean the subject matter. Theresa writes of her year's long battle against her son's mental illness that manifested in cutting and suicidal thoughts.

I could feel how taxed, exasperated, and at wit's end this mother was through the pages. I kept having to check how much was left in the e-book because I was getting to the point where I wasn't sure I could keep going back for more - and I didn't have to live it. How Larsen was able to sit down and relive the darkest of days to actually finish this book is a testament to how devoted she is to helping others who are going through this.

Having been a high school teacher, I am familiar with the different ways kids can "self-harm" - reading this gave me an insight as to just how horrific a cost it is to the entire family. The amount of doctors, facilities, high schools, and medications that had to be juggled were enough to break down even the strongest willed person.

Throughout the book, Larsen refers back to her son's journal, giving everyone a glimpse into the mind of the person who is suffering. These were by far the hardest passages for me to read. As an outsider, it is easy to look at these kinds of situations and think - "that person just needs to snap out of it" - or - "why don't the parents do something to stop this?" Unfortunately, the answer is neither that simple or logical.

I applaud Larson for putting her story out there for others who might have to travel down this road. If you have a teenager who is depressed or self-harms, this book will let you know that you are not alone. Larsen could literally save you a small fortune by her insights as to what to look for in a facility.

More importantly, this book should give you hope. I am not going to call this a "spoiler," because a happy ending should not "spoil" anyone's day. In the end, Matthew seems to have gotten to a point where things were looking much brighter. There were parts of me preparing to read an end to this story that I really did not want to imagine. To Matthew's credit, along with the Larsen family who supported him along the way, that is a plot line that can hopefully stay forever in the "delete" file.

To Theresa, Matthew, and the rest of your family - my hope is that you may have many more good days than bumps in the road in your future.

http://moviesandmanuscripts.blogspot.com/search?q=theresa+larsen

Reviewed By Lit Amri for Readers’ Favorite 5.0 out of 5 stars

Cutting the Soul by Theresa Larsen is a memoir that chronicles her son’s battle with mental illness. One day, Matthew comes to her with a cut on his hand, explaining it as an accident when he was messing around with a pocket knife. However, Theresa discovers dozens of slashes covering both of his arms. Fourteen-year-old Matthew is battling severe depression and cuts himself.

This memoir is such a roller-coaster ride of emotions. The confusion, the frustration, the struggle in dealing with Matthew’s pain, finding the right psychiatrist and medications, as well as trying to predict and be prepared for when his mood swings go dangerously low and harmful; you will definitely connect with Theresa’s words and feel her pain, regardless of whether you have experienced the same difficulty or not. I couldn't put it down and every time I turned a page, I kept hoping to read about Matthew with a healthier mind, only to discover another rocky patch in his healing. Emotionally, as a reader, I’m exhausted so I can’t imagine what it must have been like for Theresa and her family, especially Matthew.

Nevertheless, Matthew is a fighter and his mind is not always a dark cloud. In fact, he is an intelligent, courageous and strong young man. Overall, this is a powerful and enlightening memoir. It serves as a priceless life lesson to anyone who has never been in that particular situation, while reminding others who have gone through the same ordeal to stay strong and prevail.

Cutting the Soul by Theresa Larsen is a memoir that chronicles her son’s battle with mental illness. One day, Matthew comes to her with a cut on his hand, explaining it as an accident when he was messing around with a pocket knife. However, Theresa discovers dozens of slashes covering both of his arms. Fourteen-year-old Matthew is battling severe depression and cuts himself.

This memoir is such a roller-coaster ride of emotions. The confusion, the frustration, the struggle in dealing with Matthew’s pain, finding the right psychiatrist and medications, as well as trying to predict and be prepared for when his mood swings go dangerously low and harmful; you will definitely connect with Theresa’s words and feel her pain, regardless of whether you have experienced the same difficulty or not. I couldn't put it down and every time I turned a page, I kept hoping to read about Matthew with a healthier mind, only to discover another rocky patch in his healing. Emotionally, as a reader, I’m exhausted so I can’t imagine what it must have been like for Theresa and her family, especially Matthew.

Nevertheless, Matthew is a fighter and his mind is not always a dark cloud. In fact, he is an intelligent, courageous and strong young man. Overall, this is a powerful and enlightening memoir. It serves as a priceless life lesson to anyone who has never been in that particular situation, while reminding others who have gone through the same ordeal to stay strong and prevail.

5.0 out of 5 stars Powerful and Emotional

"Cutting the Soul by Theresa Larsen is a powerful and emotional memoir of her son's mental illness and her struggles to cope with keeping him safe and well.

The book is an enlightening read for anyone not familiar with self-harming (cutting) and psychosis along with the treatment options available for each. Ultimately, a mixture of parental love and years of treatment helped this young man to cope with his disorder. At times the book was graphic in nature, but only to bring home a point - mental illness is a harsh and unrelenting malady and often takes years to get under control with medication, counseling and a great deal of family support. The message here is to never give up and to remain hopeful even in the darkest moments. Ms. Larsen has shown that there can be a good outcome to years of treatment.

I applaud the author for bringing her story of a mothers' love in dealing with the issues of a mentally ill child to the public."--S.A. Molteni

"Cutting the Soul by Theresa Larsen is a powerful and emotional memoir of her son's mental illness and her struggles to cope with keeping him safe and well.

The book is an enlightening read for anyone not familiar with self-harming (cutting) and psychosis along with the treatment options available for each. Ultimately, a mixture of parental love and years of treatment helped this young man to cope with his disorder. At times the book was graphic in nature, but only to bring home a point - mental illness is a harsh and unrelenting malady and often takes years to get under control with medication, counseling and a great deal of family support. The message here is to never give up and to remain hopeful even in the darkest moments. Ms. Larsen has shown that there can be a good outcome to years of treatment.

I applaud the author for bringing her story of a mothers' love in dealing with the issues of a mentally ill child to the public."--S.A. Molteni

5* Review by Cheryl S.

I read this book many months ago but the words on the pages continue to float through my mind daily and in my dreams at night. The depth that Theresa reaches with her words are life changing. Mental Illness at any age is difficult but to experience it at such a young age is heart breaking. Being a teenager is tough enough and parenting those teenagers is a challenge on any given day. Add mental illness to the challenge and many people would cave in and/or give up. Theresa's determination and unrelenting love for her son teaches us all what being a parent is all about. Loving unconditionally! Matthew's determination to continue his daily survival and defeat his demons may be a life long struggle but knowing he has his mom in his corner must give him the reassurance he needs to know life is worth living. This book has such a powerful message and should be read by all.

I read this book many months ago but the words on the pages continue to float through my mind daily and in my dreams at night. The depth that Theresa reaches with her words are life changing. Mental Illness at any age is difficult but to experience it at such a young age is heart breaking. Being a teenager is tough enough and parenting those teenagers is a challenge on any given day. Add mental illness to the challenge and many people would cave in and/or give up. Theresa's determination and unrelenting love for her son teaches us all what being a parent is all about. Loving unconditionally! Matthew's determination to continue his daily survival and defeat his demons may be a life long struggle but knowing he has his mom in his corner must give him the reassurance he needs to know life is worth living. This book has such a powerful message and should be read by all.

"In a gripping memoir, the author tells

of a few years in the life of a mentally ill child, along with the concerns,

fears, and revelations of his mother. For much of the story I found myself

holding my breath, silently praying that the child continues to stay alive.

Like the mother, I grew to fear that one of the cutting incidents would lead to

his suicide. The story unfolds in a natural way that takes readers along for

the entire emotional journey. The story is one that should be in the hands of

every parent whose child has challenges of any kind."--editor review

"The emotional story of a mother's overwhelming challenge of mental illness in her teenage son becomes a gripping suspense tale and truly a page turner. The rocky road to find help while awaiting what might well be the next and final episode of self hurting opens a whole new window into this world that few of us have a clue about."--Amazon Customer 5*

"A must read for anyone you know who has a troubled teenager. A compassionate tale of real life battling the baffling web of mental illness. Learn from and share the roller coaster ride of the mental health system and the internal conflicts of what a mother is to do with a bright and talented son who is haunted by demons that lead him to self injury. A "cutter" can be a pariah to the normal avenues of mental health treatment which leaves you where?

In an of itself, it is a true page turner from the first chapter. A good read that leaves you shaken, yet educated on an area that you may not have been exposed to.

A first book by a gifted writer who has found herself and her son." --fredh3 5*

"Great read into mental illness with a teenager. Gives an inside view of a life that I never even thought about. Very relevant for the times we live in. Must read."--Barbara Silver 5*

"Great read. Roller coaster ride of non-fiction with very helpful insite for parents and family of a child with mental health issues. Highly recommend it." --Vortex Reviews 4*

"This is an extremely important book for anyone who cares for someone suffering from mental illness. If you haven't been touched by this disease, you will be touched by one mother's determination, will and love for her child to do what was necessary---even when necessary was heartbreaking. Cutting the soul is an honest,open and emotionally jarring read with the power to offer hope and resources to those who need it and don't know where to turn."--Thomas Phillips 5*

"This book is so current and relative for any parent today. Whether we know it or not, our teens may be struggling with some level of depression or mental illnesss. The author is so relatable. I could picture myself responding to her circumstances in the same way she did. Her openness encourages parents to recognize mental illness and seek proper treatment."--Sheri C. 5*

"Cutting the Soul: This is a must read for parents of teenagers and anyone dealing with mental illness. Theresa Larsen bears her soul in “Cutting the Soul” to tell the story of her son Matthew’s self harming and mental illness. Not only does Theresa tell of her son’s struggles, she also provides resources for mental health help. This book was an emotional roller coaster, but well worth the ride."--Leslie G. 5*

"A well written account of an actual child's struggle, his family's ability to cope and the results of the painful "stops and starts" along the way. All wrapped in a blanket of great love, caring and hope."--Stormy 5*

"Whether or not you are close to a troubled child, you will not fail to experience the acute emotions and feelings of this heroic mother and son as they struggle to deal with his strange affliction. With beautiful writing skill, Ms. Larsen delivers a gripping chronicle of the day to day triumphs and tragedies they experienced over several years of his childhood. You will laugh and cry along with them, and emerge with a new appreciation of the human spirit."--Amazon Customer 5*

"This book was a selection for my book club and I wasn't sure I wanted to read about a teenage "cutter". Fortunately, I did read this story which is so much more. It gives you an appreciation for the struggles of anyone dealing with mental illness. Beyond the shock of learning of her son's illness, Theresa discovers the difficulties of navigating the maze of the medical profession, insurance, schools and society. It is a must read for anyone caring for someone with a chronic condition.

Being told from a mother's perspective gives the reader both gut retching and heart warming moments. The trauma of the son is a trauma for all of the family. Their story is inspiring. This well written narrative will leave you with much food for thought."--Carolyn 5*

"Hard to imagine a subject more challenging and difficult to write about, yet so needed. The author takes you through the maze of the mental health system and with great honesty and compassion guides you through her harrowing experience. It makes for an even better read that there is humor and humility used throughout as well as some amazing examples of how to get through raising a child with a mental health diagnosis while keeping your own sanity. I enjoyed this book and found it to be a page turner and a recommended read for all."--Cheryl F. 5*

"As a professional in the mental health field this book was very insightful. It isn't often you get a glimpse into mental illness from the perspective of a parent. Mrs Larsen is able to pull the reader into the story right away. I couldn't put it down!"--Eric F. 5*

"A must read for anyone entering the psychiatric or counseling profession. Invaluable insight from a parent's perspective--well written with great flow."--YoYo 5*

"Well written and hard to put down...a courageous account of a family that did not quit in their support, love, and self examination in their sons' dark mental illness; equally complex to figure out the best way to help him. Difficult to read at times and forced me to consider some of my own misguided attitudes about mental health. Painfully honest."--Joanne D. 4*

"I could not put it down! It was an amazing look at the struggles your family faced---it was captivating! Thank you for sharing your private life in a way that can possibly open up a dialogue for others! I have several good friends that have suffered similarly both in the parent and child role. There certainly needs to be more assistance and information out there available!! God Bless You!"--Arthur M. 5*

"A compelling book about the journey of dealing with the severe mental illness of a child. Good for both treating professionals and parents of ill children."--Sandra 4*

"The emotional story of a mother's overwhelming challenge of mental illness in her teenage son becomes a gripping suspense tale and truly a page turner. The rocky road to find help while awaiting what might well be the next and final episode of self hurting opens a whole new window into this world that few of us have a clue about."--Amazon Customer 5*

"A must read for anyone you know who has a troubled teenager. A compassionate tale of real life battling the baffling web of mental illness. Learn from and share the roller coaster ride of the mental health system and the internal conflicts of what a mother is to do with a bright and talented son who is haunted by demons that lead him to self injury. A "cutter" can be a pariah to the normal avenues of mental health treatment which leaves you where?

In an of itself, it is a true page turner from the first chapter. A good read that leaves you shaken, yet educated on an area that you may not have been exposed to.

A first book by a gifted writer who has found herself and her son." --fredh3 5*

"Great read into mental illness with a teenager. Gives an inside view of a life that I never even thought about. Very relevant for the times we live in. Must read."--Barbara Silver 5*

"Great read. Roller coaster ride of non-fiction with very helpful insite for parents and family of a child with mental health issues. Highly recommend it." --Vortex Reviews 4*

"This is an extremely important book for anyone who cares for someone suffering from mental illness. If you haven't been touched by this disease, you will be touched by one mother's determination, will and love for her child to do what was necessary---even when necessary was heartbreaking. Cutting the soul is an honest,open and emotionally jarring read with the power to offer hope and resources to those who need it and don't know where to turn."--Thomas Phillips 5*

"This book is so current and relative for any parent today. Whether we know it or not, our teens may be struggling with some level of depression or mental illnesss. The author is so relatable. I could picture myself responding to her circumstances in the same way she did. Her openness encourages parents to recognize mental illness and seek proper treatment."--Sheri C. 5*

"Cutting the Soul: This is a must read for parents of teenagers and anyone dealing with mental illness. Theresa Larsen bears her soul in “Cutting the Soul” to tell the story of her son Matthew’s self harming and mental illness. Not only does Theresa tell of her son’s struggles, she also provides resources for mental health help. This book was an emotional roller coaster, but well worth the ride."--Leslie G. 5*

"A well written account of an actual child's struggle, his family's ability to cope and the results of the painful "stops and starts" along the way. All wrapped in a blanket of great love, caring and hope."--Stormy 5*

"Whether or not you are close to a troubled child, you will not fail to experience the acute emotions and feelings of this heroic mother and son as they struggle to deal with his strange affliction. With beautiful writing skill, Ms. Larsen delivers a gripping chronicle of the day to day triumphs and tragedies they experienced over several years of his childhood. You will laugh and cry along with them, and emerge with a new appreciation of the human spirit."--Amazon Customer 5*

"This book was a selection for my book club and I wasn't sure I wanted to read about a teenage "cutter". Fortunately, I did read this story which is so much more. It gives you an appreciation for the struggles of anyone dealing with mental illness. Beyond the shock of learning of her son's illness, Theresa discovers the difficulties of navigating the maze of the medical profession, insurance, schools and society. It is a must read for anyone caring for someone with a chronic condition.

Being told from a mother's perspective gives the reader both gut retching and heart warming moments. The trauma of the son is a trauma for all of the family. Their story is inspiring. This well written narrative will leave you with much food for thought."--Carolyn 5*

"Hard to imagine a subject more challenging and difficult to write about, yet so needed. The author takes you through the maze of the mental health system and with great honesty and compassion guides you through her harrowing experience. It makes for an even better read that there is humor and humility used throughout as well as some amazing examples of how to get through raising a child with a mental health diagnosis while keeping your own sanity. I enjoyed this book and found it to be a page turner and a recommended read for all."--Cheryl F. 5*

"As a professional in the mental health field this book was very insightful. It isn't often you get a glimpse into mental illness from the perspective of a parent. Mrs Larsen is able to pull the reader into the story right away. I couldn't put it down!"--Eric F. 5*

"A must read for anyone entering the psychiatric or counseling profession. Invaluable insight from a parent's perspective--well written with great flow."--YoYo 5*

"Well written and hard to put down...a courageous account of a family that did not quit in their support, love, and self examination in their sons' dark mental illness; equally complex to figure out the best way to help him. Difficult to read at times and forced me to consider some of my own misguided attitudes about mental health. Painfully honest."--Joanne D. 4*

"I could not put it down! It was an amazing look at the struggles your family faced---it was captivating! Thank you for sharing your private life in a way that can possibly open up a dialogue for others! I have several good friends that have suffered similarly both in the parent and child role. There certainly needs to be more assistance and information out there available!! God Bless You!"--Arthur M. 5*

"A compelling book about the journey of dealing with the severe mental illness of a child. Good for both treating professionals and parents of ill children."--Sandra 4*

Excerpts

Year 1-Chapter 1-A Broken Soul

Sometimes you are so low that you don’t know how to pick yourself up. All you want to do is crawl in a corner and die. Most days are like that for my son.

***

“Mom, I cut my hand.”

“What? Let me see,” I said.

“Don’t be angry at me, please. I was messing around with my pocket knife and I cut my hand. I didn’t mean to cut it this deep. It hurts so bad,” whimpered Matthew. Matthew showed me the slice on his right hand. On the fleshy part of the palm below the thumb, a deep gash was visible. The wound had stopped bleeding, but it looked nasty.

I yanked him into my bathroom and pulled the hydrogen peroxide and cotton balls out of the cabinet. “Wash your hands under the faucet,” I urged. Matthew winced as the water hit the cut. I joined him at the sink. He had the long-sleeves of his shirt pulled over his hands and he held the cuff of each sleeve against his palm with his pinky and ring finger. “Pull your sleeves up,” I said.

He hesitated, stopped washing his hands, and froze.

I reached toward him and pulled at his sleeves. Slashes covered both arms. Each horizontal mark on the inside of his wrist to his upper forearm measured about two inches in length, and a quarter of an inch apart; dozens of raw, bleeding lines. After a sharp intake of breath, I blurted, “What the hell have you done?”

Matthew looked sheepish and replied, “I was trying something. It hurts so bad, I will never do it again.”

I didn’t know what to say. I had heard of kids cutting themselves, but I found self-harm impossible to understand.

My husband, Erik, Matthew’s step-father, entered the bathroom. We had been married four years and even though he did not have children of his own he treated my children, Jessica and Matthew, as his own. “Look at Matthew’s arms.” I exclaimed.

“Were you trying to kill yourself?” Erik asked perplexed.

Looking at the floor, Matthew replied, “No.”

“Then what is this?” Erik questioned.

Matthew once again muttered, “I was just trying something.”

I couldn’t understand what he meant, and I guess Matthew couldn’t either, because he didn’t have any other words to describe his behavior.

By Matthew’s fourteenth birthday, he stood over six feet tall and weighed one-hundred and forty pounds. He had thick, dark hair and an olive skin tone. His dark eyes had a sad quality. Matthew’s intelligence was subtle. He’d listen, unobserved, to a conversation, interject a quick, clever comment, and walk away, leaving those in the conversation stunned. Matthew played guitar, piano, and loved to draw. He was sensitive and kind, but easily offended and emotionally vulnerable. He often had high expectations and unrealistic goals for himself that he couldn’t always achieve. Not reaching those goals made him angry and ashamed. Cutting himself wasn’t the first mark of troubled emotions. He had been depressed on and off for many months. The depression wasn’t always outwardly noticeable, but the signs were there. He didn’t want to go to school, or complete his homework. He often isolated himself in his room listening to questionable music. Physically hurting himself was new. We were also shocked by its timing. Our family had recently returned from an enjoyable New Year’s ski vacation.

“Internalize everything I see. Eternity remembers me. Frozen imperial city. Bridge you. A cornerstone for justice. Insincerely just this. A broken soul for all to know, torn and thrown. Cornerstone. Now you know why I do this. It’s all crushed, broken pieces. Satisfaction guaranteed. Righteous thesis. This is all I need. Fallen.”--Matthew’s journals

An ER visit did not seem necessary, so I bandaged Matthew’s hand, cleaned the other wounds, and left everything for the night. If I had known what I know now, instead of lying in bed that night trying to sleep, I might have done things differently. I never dreamed how many more sleepless nights I would have to endure in the years to come.

The next morning, I drove Matthew to the pediatrician. A kind and understanding female doctor said his hand needed stitches. An open door to the hallway allowed the office assistants to see Matthew’s arms as his hand was stitched. His limbs looked like ragged pieces of meat; raw, red, and inflamed. The office assistants whispered, shook their heads, and nudged others to look at the boy with the slashed arms. I felt judged. What kind of mother let their child do such a thing to himself? What was wrong with us?

Psychiatric referrals were provided after my request. The doctor neither suggested Matthew be admitted to the hospital for a psychiatric evaluation, nor that he be Baker Acted. The Florida Mental Health Act of 1971 states “The Baker Act allows for involuntary examination. It can be initiated by judges, law enforcement officials, physicians, or mental health professionals. There must be evidence that the person: has a mental illness (as defined in the Baker Act); is a harm to self, harm to others, or self-neglectful (as defined in the Baker Act).”

Didn’t the description define Matthew? Wasn’t he a harm to himself? I had no idea of how to proceed, and later, I wondered why we were not given instructions on the Baker Act. Shouldn’t doctors provide parents with that option when they see a patient who has self-harmed? Shouldn’t they arm parents with all available information?

No one in our family had ever been to a psychiatrist, so when I was able to arrange an appointment for the following day I wondered if it was a bad sign. We sat in the waiting room while Matthew texted friends telling them he was in a psychiatrist’s office because he had cut himself. I found his reaction bizarre. Why tell his friends? He apparently didn’t mind who knew. Matthew looked at me as I jiggled my feet in nervous anxiety, and asked, “What’s wrong?” I inhaled, rubbed my hand across my forehead, exhaled, and said, “What do you think is wrong? I am worried about you. We are in a psychiatrist’s office after you cut your arms. How can you not know what is wrong?”

Matthew shrugged and said, “Oh.”

Dr. Manning led us into her office and asked Matthew questions about how he felt and then requested he fill out a few questionnaires. It seemed rehearsed; the standard procedure for each patient. She didn’t ask to see his arms or discuss whether he was suicidal. In her fifteen minutes of analysis, it was decided that Matthew required medication to help with his depressive mood. She wrote a prescription, and we left the office after making a follow-up appointment. Jumping right into medication without trying another approach seemed less than thorough, so I delayed filling the prescription. We needed more time to decide on the best method of treatment.

Fortunately, I played tennis at our local club. Tennis was a good physical and mental challenge, and it also gave me a social outlet. Playing gave me a great deal of personal satisfaction and served as therapy each moment I stepped on the court. I worked hard to learn correct techniques and skills to advance on the “tennis ladder.” Everyone needs a “thing” to keep the mind and body active. I’m not sure I would have survived without mine.

(all names and places have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals)

Sometimes you are so low that you don’t know how to pick yourself up. All you want to do is crawl in a corner and die. Most days are like that for my son.

***

“Mom, I cut my hand.”

“What? Let me see,” I said.

“Don’t be angry at me, please. I was messing around with my pocket knife and I cut my hand. I didn’t mean to cut it this deep. It hurts so bad,” whimpered Matthew. Matthew showed me the slice on his right hand. On the fleshy part of the palm below the thumb, a deep gash was visible. The wound had stopped bleeding, but it looked nasty.

I yanked him into my bathroom and pulled the hydrogen peroxide and cotton balls out of the cabinet. “Wash your hands under the faucet,” I urged. Matthew winced as the water hit the cut. I joined him at the sink. He had the long-sleeves of his shirt pulled over his hands and he held the cuff of each sleeve against his palm with his pinky and ring finger. “Pull your sleeves up,” I said.

He hesitated, stopped washing his hands, and froze.

I reached toward him and pulled at his sleeves. Slashes covered both arms. Each horizontal mark on the inside of his wrist to his upper forearm measured about two inches in length, and a quarter of an inch apart; dozens of raw, bleeding lines. After a sharp intake of breath, I blurted, “What the hell have you done?”

Matthew looked sheepish and replied, “I was trying something. It hurts so bad, I will never do it again.”

I didn’t know what to say. I had heard of kids cutting themselves, but I found self-harm impossible to understand.

My husband, Erik, Matthew’s step-father, entered the bathroom. We had been married four years and even though he did not have children of his own he treated my children, Jessica and Matthew, as his own. “Look at Matthew’s arms.” I exclaimed.

“Were you trying to kill yourself?” Erik asked perplexed.

Looking at the floor, Matthew replied, “No.”

“Then what is this?” Erik questioned.

Matthew once again muttered, “I was just trying something.”

I couldn’t understand what he meant, and I guess Matthew couldn’t either, because he didn’t have any other words to describe his behavior.

By Matthew’s fourteenth birthday, he stood over six feet tall and weighed one-hundred and forty pounds. He had thick, dark hair and an olive skin tone. His dark eyes had a sad quality. Matthew’s intelligence was subtle. He’d listen, unobserved, to a conversation, interject a quick, clever comment, and walk away, leaving those in the conversation stunned. Matthew played guitar, piano, and loved to draw. He was sensitive and kind, but easily offended and emotionally vulnerable. He often had high expectations and unrealistic goals for himself that he couldn’t always achieve. Not reaching those goals made him angry and ashamed. Cutting himself wasn’t the first mark of troubled emotions. He had been depressed on and off for many months. The depression wasn’t always outwardly noticeable, but the signs were there. He didn’t want to go to school, or complete his homework. He often isolated himself in his room listening to questionable music. Physically hurting himself was new. We were also shocked by its timing. Our family had recently returned from an enjoyable New Year’s ski vacation.

“Internalize everything I see. Eternity remembers me. Frozen imperial city. Bridge you. A cornerstone for justice. Insincerely just this. A broken soul for all to know, torn and thrown. Cornerstone. Now you know why I do this. It’s all crushed, broken pieces. Satisfaction guaranteed. Righteous thesis. This is all I need. Fallen.”--Matthew’s journals

An ER visit did not seem necessary, so I bandaged Matthew’s hand, cleaned the other wounds, and left everything for the night. If I had known what I know now, instead of lying in bed that night trying to sleep, I might have done things differently. I never dreamed how many more sleepless nights I would have to endure in the years to come.

The next morning, I drove Matthew to the pediatrician. A kind and understanding female doctor said his hand needed stitches. An open door to the hallway allowed the office assistants to see Matthew’s arms as his hand was stitched. His limbs looked like ragged pieces of meat; raw, red, and inflamed. The office assistants whispered, shook their heads, and nudged others to look at the boy with the slashed arms. I felt judged. What kind of mother let their child do such a thing to himself? What was wrong with us?

Psychiatric referrals were provided after my request. The doctor neither suggested Matthew be admitted to the hospital for a psychiatric evaluation, nor that he be Baker Acted. The Florida Mental Health Act of 1971 states “The Baker Act allows for involuntary examination. It can be initiated by judges, law enforcement officials, physicians, or mental health professionals. There must be evidence that the person: has a mental illness (as defined in the Baker Act); is a harm to self, harm to others, or self-neglectful (as defined in the Baker Act).”

Didn’t the description define Matthew? Wasn’t he a harm to himself? I had no idea of how to proceed, and later, I wondered why we were not given instructions on the Baker Act. Shouldn’t doctors provide parents with that option when they see a patient who has self-harmed? Shouldn’t they arm parents with all available information?

No one in our family had ever been to a psychiatrist, so when I was able to arrange an appointment for the following day I wondered if it was a bad sign. We sat in the waiting room while Matthew texted friends telling them he was in a psychiatrist’s office because he had cut himself. I found his reaction bizarre. Why tell his friends? He apparently didn’t mind who knew. Matthew looked at me as I jiggled my feet in nervous anxiety, and asked, “What’s wrong?” I inhaled, rubbed my hand across my forehead, exhaled, and said, “What do you think is wrong? I am worried about you. We are in a psychiatrist’s office after you cut your arms. How can you not know what is wrong?”

Matthew shrugged and said, “Oh.”

Dr. Manning led us into her office and asked Matthew questions about how he felt and then requested he fill out a few questionnaires. It seemed rehearsed; the standard procedure for each patient. She didn’t ask to see his arms or discuss whether he was suicidal. In her fifteen minutes of analysis, it was decided that Matthew required medication to help with his depressive mood. She wrote a prescription, and we left the office after making a follow-up appointment. Jumping right into medication without trying another approach seemed less than thorough, so I delayed filling the prescription. We needed more time to decide on the best method of treatment.

Fortunately, I played tennis at our local club. Tennis was a good physical and mental challenge, and it also gave me a social outlet. Playing gave me a great deal of personal satisfaction and served as therapy each moment I stepped on the court. I worked hard to learn correct techniques and skills to advance on the “tennis ladder.” Everyone needs a “thing” to keep the mind and body active. I’m not sure I would have survived without mine.

(all names and places have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals)

Year 1--Chapter 6--An Inch Into The Pain

“A single drop makes even the strongest shudder. My own suffering caused from a powerless action. A desperate plea for the sight of my own blood. Striking the match of simple pleasures, leading myself to failure.”--Matthew’s journals

Matthew stayed in bed late the next day. I left him to sleep, hoping the rest would heal some of his emotional wounds. By one o’clock I decided he needed to face the day. I was not prepared for the blood; multiple lacerations on his forearms and thighs, a reckless attempt to quell his pain. Matthew couldn’t hide his shame. I cried and asked what we should do.

He shrugged. He was overwhelmed with misery. The cuts were not deep enough to need a doctor, so we cleaned them and applied ointment.

I called Kate and asked for her advice. She said Matthew shouldn’t come in to see her. She did not want to create a pattern of self-harming and reinforcement. We agreed to keep the appointment for the following week. She suggested removing any obvious implements Matthew could use to hurt himself. She had discovered in her therapeutic sessions that Matthew dissociated when cutting. According to medterms.com, “In psychology and psychiatry, dissociation, is a perceived detachment of the mind from the emotional state or even from the body. Dissociation is characterized by a sense of the world as a dreamlike or unreal place and may be accompanied by poor memory of specific events.” In this dreamlike state Matthew withdrew from his emotions and the pain of self-harming. Kate believed, when dissociating, Matthew might not be aware of how severe he cut himself. Kate said if Matthew had to go to the effort of finding an item to cut with and take the item apart or manipulate it, the energy spent on the item could give him an opportunity to think and be more present in the situation. The advice sounded good, but again, nobody suggested a psychiatric evaluation. If he had gone to a hospital for an evaluation after the first self-harm incident, some of the other incidents might not have happened.

After speaking with Kate I asked Matthew what he had used to cut himself.

He explained that he had taken a kitchen knife out of a drawer.

Thinking my kitchen knives would disappear one at a time, I asked what he did with it afterward.

He said he placed it in the dishwasher.

My face must have displayed my disgust at the thought of a knife that cut my child’s skin also used to slice food. Matthew sputtered, “I put it in the dishwasher; that will get it clean enough.”

Not anywhere near clean enough for me. After Matthew’s statement and Kate’s advice, I removed all the sharp knives and any other sharp items from the kitchen drawers and hid them in my closet. Not a convenient way to prepare food, but a little safer.

Matthew was quiet for most of the day, but the severe sadness and anger we had seen in him the previous day was suppressed, an emerging pattern after self-harm. Cutting himself apparently gave him a release from his emotional turmoil, and then he could cope better. It was weirdly logical, but dangerous.

I called a handyman to come out the following day and install locks on a cabinet in the family room. I also bought a combination lock box at the local office supply store. In the cabinet I crammed the kitchen knives, skewers, ice picks, corn cob holders, wine openers, bottle openers, scissors, potato peelers, razor blades, prescription medication, and pencil sharpeners. Yes, even pencil sharpeners. They have a razor blade inside that is easily dislodged. Into the cabinet went anything I could think of that Matthew could use to hurt himself. I locked the cabinet with the key and locked the key in the combination box. When I needed to slice a tomato I had to dial the combination of the box, remove the key, go to the cabinet, unlock it, take a knife, lock it again, return the key to the combination box, and set the combination.

Once I used the knife and cleaned it, I had to repeat the whole process in reverse. Needless to say we didn’t cut many things for meals. I found many ways to avoid chopping food and found clever ways to use a fork.

The day the handyman arrived, Matthew went to his friend’s house. Visiting a friend brought him some joy, and we looked for joy in his life anywhere we could find it.

That Saturday we took Matthew with us to stay in North Florida for a night. We got away to regain a little peace in our lives. Matthew brought his guitar, sat on the porch, and played music while Erik and I tried to relax. The burden of responsibility for Matthew weighed heavily on Erik and me. We wanted to keep Matthew safe, but weren’t sure how to accomplish that twenty-four hours a day. When he was at school or with friends, he was busy and happier and didn’t experience feelings of desperation or have an urge to cut himself. The evenings and nights worried me the most. I knew I could cope with the daylight hours, but not the night, not when we slept and couldn’t watch him.

***

Matthew’s next appointment with Dr. Andrews was on Monday. Dr. Andrews prescribed 25 milligrams of Zoloft for depression. It had been six long months since the first self-harm incident. I had come to terms with the need for medication.

We were in the process of preparing our bonus room above the garage as Matthew’s bedroom. Jessica and Matthew had always shared a bathroom between their bedrooms. Jessica recently turned thirteen and Matthew was almost fifteen. The time for sharing a bathroom had come and gone. We had the space, and the extra bathroom, so moving was the next step. Matthew helped pick paint colors for his new room, and we decided to go shopping later in the week for extra furniture he needed. The thrill of a new space excited Matthew and was a welcome distraction from our everyday life.

The next day Matthew stayed in bed until noon. I begged him to get up and eat, because he had a therapy appointment at two o’clock.

Matthew refused to speak.

I pleaded with him. He shook his head and stayed mute all day.

I called Kate, explained our situation and apologized. She understood and said she had an opening the next day and could see Matthew then.

I couldn’t figure out what had changed from the day before. Why would he be happy one day and unhappy the next? I wanted to figure out a pattern in his moods. When Matthew didn’t speak to me I had no way of knowing what was going on inside his head.

Matthew spent most of the day in his bedroom playing video games or playing a guitar. He ate dinner with us, but still refused to speak. I gave him some boxes and asked him to pack the items in his old room, so we could move them to his new room. Matthew lay on the bed and stared at the ceiling.

I asked him again to pack. I left the room. A few minutes later I heard a loud commotion coming from Matthew’s room. Erik and I found Matthew throwing things off his desk and breaking other items.

“Stop!” I shouted.

When all the items from the desk were on the floor, Matthew flung himself onto his bed.

Erik and I talked to him, with no response. Matthew’s breathing was heavy, and he was obviously troubled. We sat on the floor in his room for an hour while his tantrum abated and he succumbed to sleep. When his breathing was slow and regulated, Erik and I quietly left.

In the privacy of our room, Erik and I discussed the changes in Matthew and the fact that we had several weeks of summer left, and we weren’t sure how to cope. The unpredictability of Matthew’s moods left us void of energy and wondering what would be our breaking point. With no solutions, we were unprepared for the future.

Matthew woke much better the next day. He was speaking again and attended his appointment with Kate. Kate warned me in private to keep my “mom radar” up. She said Matthew was shifting in a negative direction. That was all I needed--for life to get worse.

The following day Matthew and I bought the other pieces of furniture for his new room. I asked a family member, Douglas, to help us assemble the furniture. He was several years older than Matthew and helpful with projects. Matthew acted immature around him, and Douglas often teased Matthew. If I had known what I know now, I would never have allowed Douglas into my house.

Erik, Douglas, and Matthew constructed a shelving unit and bolted it to a wall. The rest of the furniture was easy to set up, and the room quickly took shape. The walls were painted three colors, tan, black, and vermillion. Erik was skeptical of Matthew’s paint choices, but they worked together with his black furniture and red accents. By the end of the next day, Matthew’s room was complete; he was all moved in, and in an excellent mood.

When Matthew was in a good mood, I would be lolled into a sense of well-being. I overlooked how challenging he had been and focused on how good he was at that moment. I don’t know why; ignoring the past could have been a defense mechanism to cope with future difficulties. It was a defense mechanism I used often and one that I would have to overcome in the future.

“A single drop makes even the strongest shudder. My own suffering caused from a powerless action. A desperate plea for the sight of my own blood. Striking the match of simple pleasures, leading myself to failure.”--Matthew’s journals

Matthew stayed in bed late the next day. I left him to sleep, hoping the rest would heal some of his emotional wounds. By one o’clock I decided he needed to face the day. I was not prepared for the blood; multiple lacerations on his forearms and thighs, a reckless attempt to quell his pain. Matthew couldn’t hide his shame. I cried and asked what we should do.

He shrugged. He was overwhelmed with misery. The cuts were not deep enough to need a doctor, so we cleaned them and applied ointment.

I called Kate and asked for her advice. She said Matthew shouldn’t come in to see her. She did not want to create a pattern of self-harming and reinforcement. We agreed to keep the appointment for the following week. She suggested removing any obvious implements Matthew could use to hurt himself. She had discovered in her therapeutic sessions that Matthew dissociated when cutting. According to medterms.com, “In psychology and psychiatry, dissociation, is a perceived detachment of the mind from the emotional state or even from the body. Dissociation is characterized by a sense of the world as a dreamlike or unreal place and may be accompanied by poor memory of specific events.” In this dreamlike state Matthew withdrew from his emotions and the pain of self-harming. Kate believed, when dissociating, Matthew might not be aware of how severe he cut himself. Kate said if Matthew had to go to the effort of finding an item to cut with and take the item apart or manipulate it, the energy spent on the item could give him an opportunity to think and be more present in the situation. The advice sounded good, but again, nobody suggested a psychiatric evaluation. If he had gone to a hospital for an evaluation after the first self-harm incident, some of the other incidents might not have happened.

After speaking with Kate I asked Matthew what he had used to cut himself.

He explained that he had taken a kitchen knife out of a drawer.

Thinking my kitchen knives would disappear one at a time, I asked what he did with it afterward.

He said he placed it in the dishwasher.

My face must have displayed my disgust at the thought of a knife that cut my child’s skin also used to slice food. Matthew sputtered, “I put it in the dishwasher; that will get it clean enough.”

Not anywhere near clean enough for me. After Matthew’s statement and Kate’s advice, I removed all the sharp knives and any other sharp items from the kitchen drawers and hid them in my closet. Not a convenient way to prepare food, but a little safer.

Matthew was quiet for most of the day, but the severe sadness and anger we had seen in him the previous day was suppressed, an emerging pattern after self-harm. Cutting himself apparently gave him a release from his emotional turmoil, and then he could cope better. It was weirdly logical, but dangerous.